Understanding Male Flexibility

Flexibility, the absolute range of movement in a joint or series of joints, is a crucial component of physical health, affecting everything from athletic performance to injury prevention and daily functional mobility. While often associated with activities like yoga or gymnastics, a healthy range of motion is vital for everyone. For men, understanding the intrinsic physiological factors that dictate this range is key to both appreciating current capabilities and identifying areas for improvement. This article delves into the primary biological determinants that shape a man’s natural flexibility.

The Role of Joint Structure

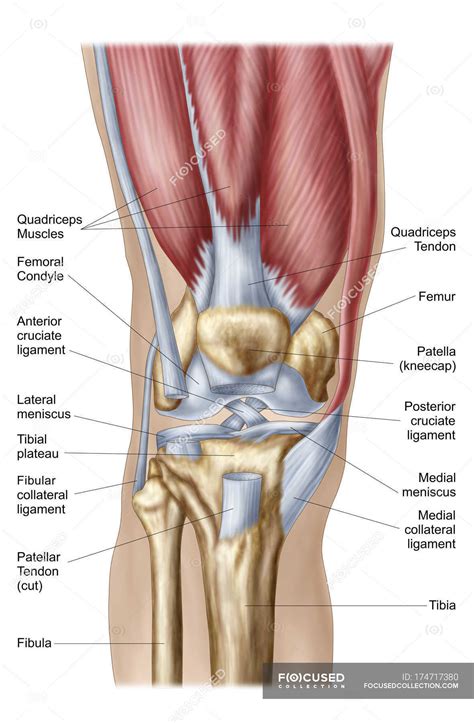

The very architecture of our skeletal system plays a fundamental role in determining flexibility. Joints are the meeting points of bones, and their design dictates the type and extent of movement possible. Different joint types, such as hinge joints (e.g., knee, elbow) which primarily allow movement in one plane, or ball-and-socket joints (e.g., hip, shoulder) which permit movement in multiple planes, inherently have different ranges of motion. The shape of the articulating bones themselves, along with the depth of the joint socket, can mechanically limit how far a limb can move. For instance, a deep hip socket provides greater stability but may naturally restrict the extreme range of motion compared to a shallower one.

Connective Tissues: The Body’s Elastic Bands

Beyond bone structure, the elasticity and extensibility of various connective tissues are paramount. These include ligaments, tendons, fascia, and the joint capsule itself.

- Ligaments: These strong, fibrous bands connect bone to bone, providing stability to joints. While they have some elasticity, their primary role is to prevent excessive or unwanted movement, acting as natural “stop signs.” Overstretching can permanently elongate ligaments, leading to joint instability.

- Tendons: Connecting muscle to bone, tendons are also somewhat elastic but less so than muscle tissue. Their flexibility is more about transmitting force than allowing significant elongation during stretches.

- Fascia: A web-like connective tissue that surrounds muscles, groups of muscles, blood vessels, and nerves, binding some structures together while permitting others to slide smoothly over each other. Tight fascia can significantly restrict muscle movement and overall flexibility.

- Joint Capsules: These fibrous sacs enclose joints, containing synovial fluid and providing both stability and a degree of flexibility. The thickness and elasticity of the capsule can influence joint range of motion.

Muscle Mass and Elasticity

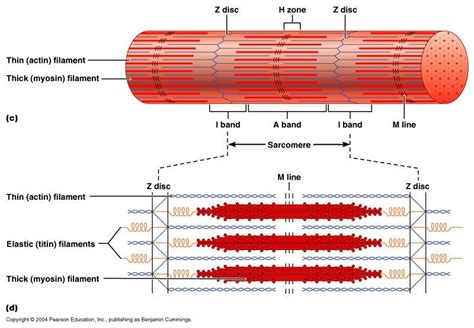

The size and extensibility of muscle tissue are significant factors. Men generally have a higher muscle mass percentage than women, which can sometimes be perceived as a limitation to flexibility. Large muscle bellies, particularly in areas like the thighs or chest, can physically obstruct the full range of motion in certain movements. However, it’s not simply the amount of muscle but its elasticity and ability to lengthen that truly matters. Muscles that are regularly stretched maintain greater extensibility, while tight, underused, or overtrained muscles can become shortened and less pliable, thus restricting flexibility.

Muscle elasticity refers to the ability of a muscle to return to its original length after being stretched. This quality is influenced by the composition of muscle fibers and the surrounding connective tissue within the muscle itself (endomysium, perimysium, epimysium).

The Nervous System’s Influence

The nervous system plays a vital, often underestimated, role in controlling flexibility. It’s not just about the physical stretch of tissues; the brain and spinal cord actively regulate how far a muscle will allow itself to be stretched to prevent injury.

- Stretch Reflex (Myotatic Reflex): When a muscle is stretched too rapidly or too far, sensory receptors called muscle spindles detect the change in muscle length. This triggers a reflex contraction of the same muscle, opposing the stretch. This protective mechanism limits immediate flexibility.

- Golgi Tendon Organ (GTO): Located in the tendons, GTOs detect tension in the muscle. When tension becomes too high (e.g., during a prolonged stretch), the GTOs send signals to the spinal cord that inhibit the contraction of the muscle and facilitate its antagonist, allowing the muscle to relax and lengthen. This is why holding a stretch for a period can increase flexibility.

![Figure 1.5, [A simple reflex circuit, the...]. - Neuroscience - NCBI Bookshelf | Neuroscience ...](/images/aHR0cHM6Ly90czMubW0uYmluZy5uZXQvdGg/aWQ9T0lQLmhyd1BaWklySzlXNTMwcnp5V1RKY1FIYUZEJnBpZD0xNS4x.webp)

Age and Other Contributing Factors

Flexibility generally declines with age. As men grow older, collagen fibers within connective tissues become more cross-linked and rigid, reducing their elasticity. Muscles may also lose some of their extensibility. However, this decline is not inevitable and can be mitigated with consistent stretching and physical activity.

Other factors influencing a man’s flexibility include:

- Genetics: Some individuals are naturally more flexible due to genetic predispositions affecting collagen type and tissue elasticity.

- Activity Level: Regular physical activity, especially movements that take joints through their full range of motion, helps maintain and improve flexibility. Sedentary lifestyles contribute to stiffness.

- Temperature: Warm muscles and connective tissues are more pliable than cold ones, which is why warming up before stretching is crucial.

- Injury History: Previous injuries or surgeries can lead to scar tissue formation and altered joint mechanics, thereby limiting flexibility.

Conclusion

A man’s natural range of flexibility is a complex outcome of multiple intertwined physiological factors. From the inherent design of his joints and the structural integrity of his connective tissues to the extensibility of his muscles and the protective reflexes orchestrated by his nervous system, each element plays a critical role. While some factors like age and genetics are largely beyond control, understanding these determinants empowers men to proactively engage in strategies—such as consistent stretching, targeted mobility work, and maintaining an active lifestyle—to optimize and maintain their flexibility, contributing to overall physical well-being and reducing the risk of injury throughout life.